KAIMOKU-SHŌ

Opening eyes and making a vow

Completed in the 9th year of Bun’ei (1272), Kaimoku-shō is one of the longest and most important of all the works authored by Nichiren Shōnin.

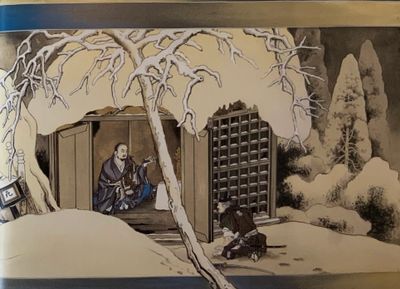

Having harshly criticised the biased religious policies of the Shogunate as well as the corruption of the Buddhist world at the time, after repeated suppression and persecution, Nichiren Shōnin was finally arrested on 12th September in the 8th year of Bun’ei (1271) and taken to Tatsunokuchi Prison in Kamakura. Although he was to be beheaded in the dead of night, the execution was canceled at the last minute and he was instead exiled to Sado Island.

In the land of Sado, an intensely cold place at that time, Nichiren Shōnin further deepened his thinking, aiming to prove the correctness of having faith in the Lotus Sūtra and to explain to his disciples and followers, in addition to finding a convincing answer for himself, why one who keeps faith in the sūtra might suffer. For that reason, this letter, written to "open the eyes" of the people, was called Kaimoku-shō (Opening the Eyes). It was sent to Shijō Kingo, a high-ranking follower of his who had rushed to the site of his attempted execution, and had wept by his side.

The beginning of the Kaimoku-shō explores the question of who all living beings should respect as their master, teacher, and parent and what their teachings are. Then, by looking at the teachings of Confucius (Confucianism), Indian philosophy, and the Buddha’s teachings (the Buddha-dharma, or “Buddhism”), the common ideas from around the world at the time, it attempts to compare all philosophical systems and religions. The result is that the teachings of Śākyamuni Buddha are found to be the best due to their broad view of past, present, and future, and the Buddha’s teaching of "enlightenment," that is, "Buddhahood," which overcomes the sufferings of life and death. In further conclusion, among all Buddhist teachings, the teaching of the Lotus Sūtra, which preaches that the world of the Buddha is eternal and without extinction and that the attainment of Buddhahood is possible for everyone, is found to be particularly excellent.

Due to his spreading the Lotus Sūtra, Nichiren Shōnin had faced many difficulties, and the topic of the work next shifts to his own reflection (kaiko 回顧) and introspection (naisei 内省). Regarding the repeated sufferings he had encountered, Nichiren Shōnin relates that in the 13th chapter of the Lotus Sūtra (“The Difficulty of Keeping this Sūtra”) it is said that after the Buddha’s passing, the "evil age of fear" (kofu no akuse 恐怖の悪世) will arrive. He points out that it is predicted that at such a time, there will be some who endure hardships in order to spread the sūtra, and he says that the series of hardships befalling him was the realisation of that prophecy. Upon realising that his life had reflected exactly what was described in the Lotus Sūtra, Nichiren Shōnin’s realisation of and confidence in his identity as a “practitioner of the Lotus Sūtra” (hokekyō no gyōja 法華経の行者) can then be seen.

However a new question then occurs. While it is true that the Lotus Sūtra says that "the person who spreads this sūtra will inevitably suffer", it is also said in many places that such a person will be protected by heaven.

So, why was Nichiren Shōnin not protected by heaven and was only suffering?

With this question in mind, the contemplation of the Kaimoku-shō further deepens once again. In the process, a thorough examination of the narrative of the Lotus Sūtra is carried out, and it is established that the Buddha had issued a request for the sūtra to be spread five times. “I, Nichiren, may be this ‘practitioner of the Lotus Sūtra’, who responds to Śākyamuni Buddha’s request, but the practitioner of the Lotus Sūtra should be protected by heaven, and I am suffering without being protected.”

After considering this in detail, the answer to the question above is finally given.

It is answered with the reasoning that, "I am suffering and am not protected by heaven because I must suffer to atone for the bad karma I have created in the past."

Nichiren Shōnin says, "For example, the more times you forge iron, the more any hidden blemishes will be exposed. The harder you squeeze hemp seeds, the more oil you will get. In the same way, the more the Lotus Sūtra is preached, the more that retribution for the sins of my past is brought forth, which I willingly accept as compensation for them.”

In this way, the Kaimoku-shō spells out his sharp feeling of repentance (sange 懺悔). Nichiren Shōnin tends to have the image of being "aggressive" and "self-righteous", but it must be remembered that such deep self-reflection is in fact at the core of his thinking.

In expressing his repentance Nichiren Shōnin draws on the story of the Never-Despising Bodhisattva (Sadāparibhūta Bodhisattva in Sanskrit; Jōfukyō Bosatsu in Japanese), which appears in the 20th chapter of the Lotus Sūtra. Never-Despising Bodhisattva was a practitioner of the teaching that all people could attain Buddhahood which can be said to be the heart of the teaching of the Lotus Sūtra. His practice was to bow to all the people he met whilst saying, “I deeply respect you, because you will be a Buddha someday.” However, his actions were seen by the people of the time as strange, and he is said to have been repeatedly persecuted. Nichiren Shōnin superimposes his own story onto this story, speculating that Never-Despising Bodhisattva may have been in the same situation as himself.

* Note: Never-Despising Bodhisattva is also known as being a model for Kenji Miyazawa's famous poem “Ame ni Mo Makezu” (Unbeaten by the Rain). You can see Tsukamoto Shonin’s talk about it here: https://youtu.be/fogtvmitBLw *

After the above-mentioned internal reflections and repentance, Nichiren Shōnin faces the Buddha once again and renews his determination to spread the Lotus Sūtra, saying: "I will never break my vow to become the pillar of Japan, to become the eyes of Japan, and become a great vessel for Japan." In this way, Nichiren Shōnin declares in the Kaimoku-shō that he will continue to spread the teaching of the Lotus Sūtra with a strong stance that is not afraid of friction, and it ends with his bright outlook for the future.