SENJI-SHŌ

Looking carefully at the era

Senji-shō, one of the representative “Five Major Works” of Nichiren Shōnin, was written in the first year of Kenji (1275).

The previous year, the 11th year Bun’ei (1274), had been a turbulent year for both Nichiren Shōnin and for Japan. The Shogunate, having received a message from the Mongol Empire threatening the invasion of Japan by the Mongolian army, decided to seek the opinion of Nichiren Shōnin, who had long before warned of invasion by foreign enemies. For that reason, Nichiren Shōnin was suddenly pardoned from exile on Sado Island and recalled to Kamakura in April 1274.

Having been summoned by the Shogunate, Nichiren Shōnin made the prediction, "Mongolia will invade within a year," and again tried to persuade important people within the Shogunate to follow his teaching of Risshō Ankoku, that is, to establish the correct teaching in order to bring peace to the country. However, since the Shogunate did not accept his advice Nichiren Shōnin left Kamakura and moved to Mt. Minobu in May. As he had foreseen, Mongolia invaded, with the first of the Mongol Invasions, the “Battle of Bun’ei” (Bun’ei no Eki 文永の役), taking place in November.

Having gained conviction that he had been correct due to the fulfilment of his prophecy, Nichiren Shōnin wrote the Senji-shō in order to look carefully at and provide a guide for this time of turmoil.

The work begins with the sentence, “When it comes to the way in which a person should study the Buddha’s Dharma, they must necessarily learn about time first.”

If you want to learn about Buddhism, it is first necessary to know about “time”. We must identify what kind of era we are in and explain the teaching that suits that time ... This is the attitude of “selecting based on the time”, which is also the title of this work: Essay on Selecting the [Right] Time”.

This attitude of “selecting the teaching according to the time” overturned the conventional wisdom of Buddhism. It had been generally thought that when preaching Buddhism, it was the “capacity”, that is, the level of the listener that should be identified or selected (this is called “teaching according to people’s capacity” taiki sep’pō 対機説法).

Nichiren Shōnin, however, believed that rather than preaching separate teachings for each individual, a teaching which was effective for all people living together in his time period should be taught. In other words, his approach went beyond providing relief only for the individual, with his horizon expanding to the relief of society as a whole. This social perspective is Nichiren Shōnin’s unique view of Buddhism which he had consistently insisted upon from the time of his writing the Risshō Ankoku-ron. Nichiren Shōnin’s thought is beautifully expressed in the phrase “Personal happiness cannot exist until the whole world is happy” in the work “A Summary of General Theory of Farmers’ Arts” (農民芸術概論綱要) left by Kenji Miyazawa (1896-1933), who was a novelist and poet who was deeply devoted to Nichiren Shōnin.

To spread the Buddha’s teachings according to the “Selection of the Time”, and liberate all the people who live together in this era from suffering, we must identify the teachings that are appropriate for this era…So what kind of time period are we in now?

Nichiren Shōnin determined that we are in an era called “Map’pō”. Map’pō is an era which is said to begin 2,000 years after the Buddha’s death, and is a time in which Buddhism declines and falls. Furthermore, the 500 years starting at the beginning of Map’pō is considered to be a dark age in which conflicts and disasters were constant, which is called “The Age of Quarrels and Disputes” - tōjōkengo 闘諍堅固 (see the “Sūtra of the Great Assembly”, Dai-jikkyō 大集経).

At that time in Japan, the year of the Buddha's death was calculated to be 949 BCE, so it was thought that the age of Map’pō began in the 7th year of Eishō (1052). The 13th century, when Nichiren Shōnin was alive, therefore, was precisely the time of the end of the Dharma, as well as being in the 500-year period known as the Age of Quarrels and Disputes.

Then, what was the teaching that was appropriate for that era, that is, the Age of Quarrels and Disputes in the Period of the End of the Dharma? Nichiren Shōnin discerned that it was the title the Lotus Sūtra, “Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō.

When Śākyamuni Buddha taught the Lotus Sūtra, he summoned a large number of unnamed Bodhisattvas who sprang up from the Earth and entrusted them with the essence of his teaching (Chapter 21, The Supernatural Powers of the Tathāgata). The leader of these Bodhisattvas was called Bodhisattva Superior Practice (Jōgyō Bosatsu 上行菩薩). Nichiren Shōnin said, “Śākyamuni Buddha put all of Buddhism into the five characters of the Lotus Sūtra, that is, “Myō Hō Ren Ge Kyō” and gave it to Bodhisattva Superior Practice. He instructed him to spread it in the future, when the era of Map’pō had arrived and all other Buddhism had declined and fallen.”

The title of the Lotus Sūtra, “Myōhō Renge Kyō” had never been disseminated from the time of Śākyamuni Buddha’s passing until the time of Nichiren Shōnin. The Nembutsu of “Namu Amida Butsu” was actively chanted, but no one chanted the Daimoku of “Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō”.

This was because the “time” had not yet come. However, now that the era of Map’pō has arrived, it is finally time to spread the Daimoku, as the Buddha instructed Bodhisattva Superior Practice. Nichiren Shōnin was so convinced as a result of his “selection” or “identification” of the time, he declared that he would spread "Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō" as a messenger of the Buddha (hotoke no otsukai 仏の御使), and wrote with deep emotion, “How fortunate, how joyous, to think that with this unworthy body I am at this time able to plant the Buddha seed in the rice fields of people’s hearts!”

Nichiren Shōnin wrote this treatise seeking to penetrate his own beliefs, to continue his seeking of the Buddhism that the times demanded and to confirm his response to the times - that is Senji-shō.

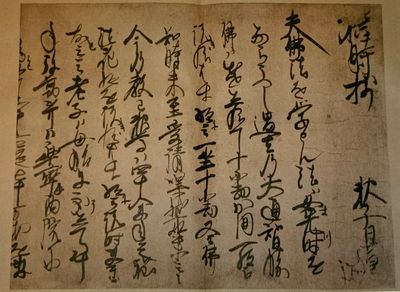

The first page of the Senji-sho, kept at Myohokkeji Temple, Mishima City, Shizuoka Prefecture.